Burnout is often associated with chronic work-related stress, leading to exhaustion and reduced efficacy. For neurodivergent individuals, such as those with conditions like Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC), Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, and other neurological differences, burnout takes on a more distinct and profound form.

To manage neurodivergent mental wellbeing and energy levels, it is important to understand the nuances of neurodivergent burnout. This article explores causes, symptoms and strategies for managing and recovering from neurodivergent burnout, offering insights and tips for neurodivergent individuals in understanding and navigating their own experiences.

What is neurodivergent burnout?

Neurodivergent burnout is a state of intense mental, emotional and physical exhaustion from the increasing toll of navigating a world that isn’t designed for you. It's not ‘just’ fatigue but a deep depletion that can lead to a temporary loss of skills, increased sensory sensitivities and significant changes in behaviour. It can feel like your internal resources are completely drained, leaving you with nothing left to give.

To understand neurodivergent burnout, it is important to note that neurodivergent individuals already operate on lower ‘spoons’ resulting in reduced energy levels compared to their counterparts. Therefore, without the necessary support, individuals are more likely to exhibit a significant co-morbidity rate for additional mental health conditions.

Why does neurodivergent burnout occur?

Neurodivergent individuals spend amounts of energy daily to navigate social expectations, process sensory information, and manage executive functions in environments that are not accommodating their needs (as in the case of lower ‘spoons’). This may include information processing, shifting and directing attention from one task to the other, cognitive flexibility, procrastination, organisation, and prioritisation. This constant mental effort often involves ‘masking’, meaning hiding of neurodivergent traits in the pursuit of fitting in. This is a main cause of burnout which often leaves individuals navigating the world outside of their Window of Tolerance.

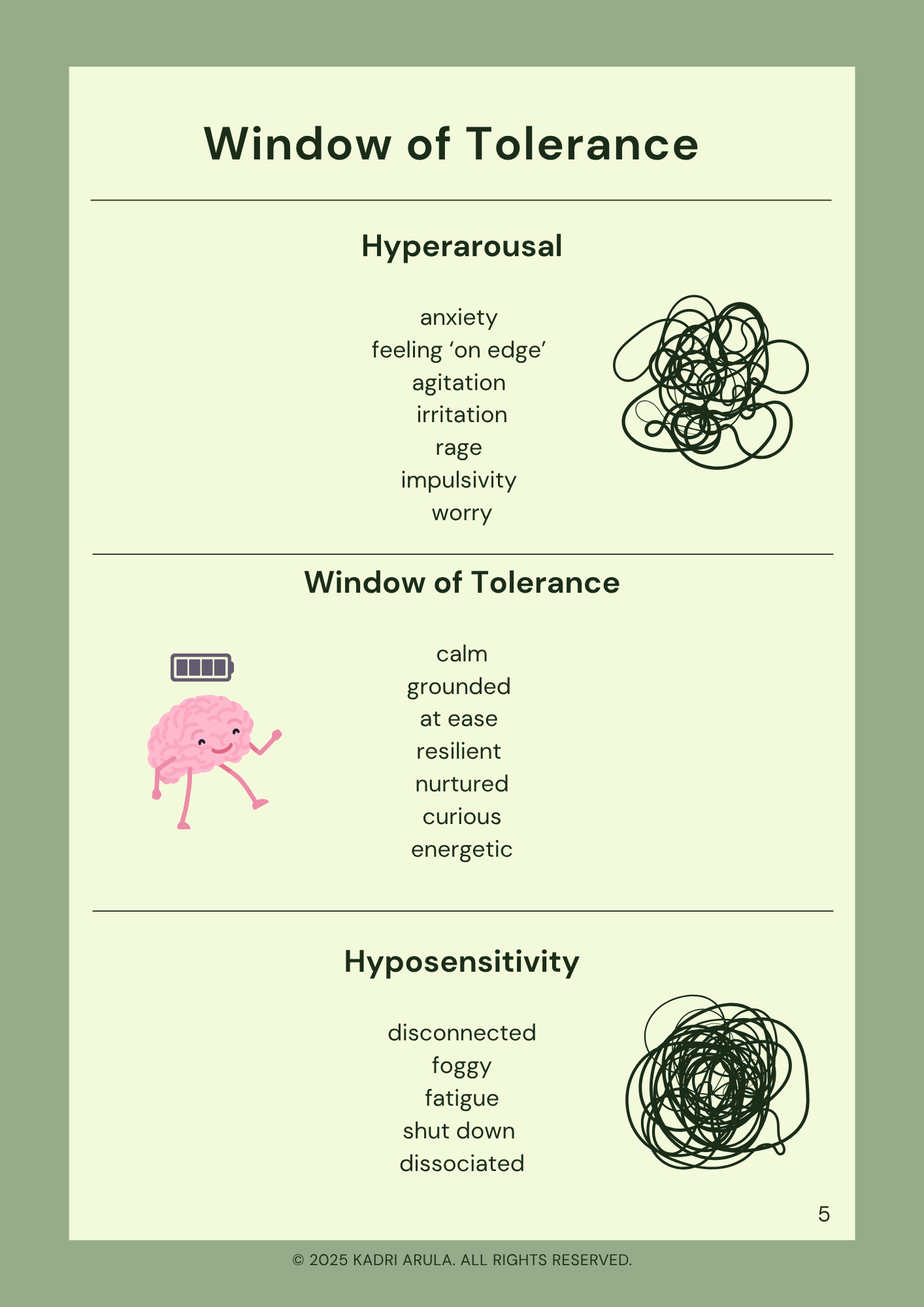

Window of Tolerance

The Window of Tolerance, originally coined by Dr. Daniel Siegel (1999), refers to the optimal zone of arousal in which an individual can function most effectively. Within this 'window,' a person can manage their emotions, thoughts and physiological responses by remaining regulated and adaptable. When someone is within their Window of Tolerance, they can effectively process information, respond thoughtfully and engage in social interactions without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down.

While a neurotypical person's Window of Tolerance can fluctuate, it generally allows for a wide range of experiences. However, for many neurodivergent individuals, their Window of Tolerance may be inherently narrower, or more easily breached, due to sensory processing needs.

Sensory processing

Many neurodivergent individuals experience heightened sensitivity (hypersensitivity) or lowered sensitivity (hyposensitivity) to various stimuli across different sensory modalities (Tomchek and Dunn, 2007). This constant exposure to overwhelming sensory input can quickly push an individual out of their window into a state of hyperarousal (fight/flight/freeze) or hypoarousal (shutdown/dissociation). This can manifest in:

Auditory sensitivities (e.g. public transport, busy office, distant sounds).

Visual sensitivities (e.g. bright or flickering lights, certain patterns, visual clutter, or direct sunlight).

Tactile sensitivities (e.g. clothing tags, rough fabrics, light touch, specific temperatures).

Olfactory (smell) sensitivities (e.g. triggers to certain smells such as strong perfumes, cleaning products, food odors, environmental smells).

Gustatory (taste) sensitivities (e.g. reactions to certain tastes or textures of food, leading to limited diets or the need for specific foods).

Proprioception (body awareness) (e.g. feeling clumsy, difficulty with motor planning,need for deep pressure).

Vestibular processing (movement, balance) (e.g. discomfort with motion, dizziness, or a strong need for spinning/rocking).

These responses may vary according to the individuals’ emotional state, surrounding environment and overall wellbeing.

When neurodivergent individuals are repeatedly pushed outside their Window of Tolerance (either into states of hyperarousal such as anxiety, meltdowns, agitation, or hypoarousal such as shutdown, dissociation, extreme fatigue) the nervous system can become chronically dysregulated. The sustained state of dysregulation significantly contributes to the profound exhaustion and depletion that is characteristic of neurodivergent burnout.

Creating your sensory soothing toolkit

Navigating neurodivergent burnout is not easy. Yet with heightened awareness, empathic understanding and with neuro-affirming strategies, recovery and long-term prevention is possible. It is about understanding and validating your own sensory needs and experiences.

In this toolkit below, I have added further information and practical tools to help you get started on sensory experiences. It is about creating a system that accommodates and accepts your needs, not a system that seeks to ‘fix’.

Conclusion

Neurodivergent burnout is tough. However, by understanding and creating awareness of your specific sensory sensitivities it is possible to have stability. By starting to create this awareness for yourself or for your loved one, validating these profound experiences can already be a start of your sensory soothing journey to navigate world with more ease, create resilience and increase mental wellbeing.

Feeling overwhelmed or experiencing neurodivergent burnout? You’re not alone. Arula Counselling offers compassionate, neuro-affirming counrselling to help you understand your individual needs.

References

Arnold, G. L., and Ryan, S. R. (2024). The nuances of neurodivergent burnout: A scoping review. In ASSETS '24: The 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (pp. 1–13). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3729176.3729193

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. Guilford Press.

Tomchek, S. D., and Dunn, W. (2007). Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 61(2), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.61.2.190